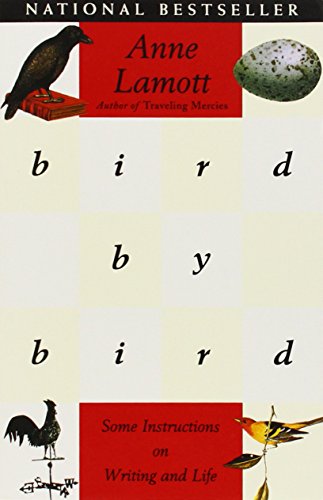

4 Writing Tips from Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird

A few tips about the craft from a master artisan.

Twenty years ago, Anne Lamott published Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. Today, it still sells like hotcakes. For the record, I’m not sure why we say “hotcakes” sell so well, but I am sure that Lamott would tell me to drop that cliché from my prose. Regardless, here are four quotes which I found provocative and helpful as I read her thoughts on the craft.

1. On the ethical, passionate center of your life and your writing:

“If you find that you start a number of stories or pieces that you don’t ever bother finishing, that you lose interest or faith in them along the way, it may be that there is nothing at their center about which you care passionately. You need to put yourself at their center, and what you believe to be true or right. The core, ethical concepts in which you most passionately believe are the language in which you are writing.” (103)

2. On writer’s block:

“We have all been there, and it feels like the end of the world. It’s like a little chickadee being hit with an H bomb. Here’s the thing, though. I no longer think of it as block. I think that is looking at the problem from the wrong angle. If your wife locks you out of the house, you don’t have a problem with the door. The word block suggests that you are constipated or stuck, when the truth is that you’re empty.” (177-8)

3. On not saving your “best” stuff for another day:

“Annie Dillard has said that day by day you have to give the work before you all the best stuff you have, not saving up for later projects. If you give freely, there will always be more. This is a radical proposition that runs so contrary to human nature, or at least contrary to my nature, that I personally keep trying to find loopholes in it. But it is only when I go ahead and decide to [go all-in] on a daily basis that I get any sense of full presence… Otherwise I am a weird little rodent squirreling things away, hoarding and worrying about supply.” (202)

4. Writing overcomes isolation:

“Becoming a writer is about becoming conscious. When you’re conscious and writing from a place of insight and simplicity and real caring about the truth, you have the ability to throw the lights on for your reader. He or she will recognize his or her life and truth in what you say, and the pictures you have painted, and this decreases the terrible sense of isolation that we have all too much of.” (226)

[Image]

The Chemical Reaction that Was, and Is, my Calling to Preach

Chemical reactions are strange things. Sometimes two ingredients that are unreactive by themselves, when combined, can become explosive, especially if shaken. This post is about two ingredients in my life that combined to create my call preach.

It’s an odd shift from Engineer to Preacher, some might say. And I suppose they could be right. It has often felt strange to me as well. When I was eighteen years old and thinking about college majors, I was far more interested in thermodynamics than homiletics. In fact, I didn’t even know what homiletics was.

So how did it happen—how and why did my interest change? Well, I’m not actually sure I will ever know all of the factors that went into the transition. In my mind, sometimes I think of it like a chemical reaction. Chemical reactions can be strange things. Sometimes two ingredients that are unreactive by themselves, when combined, become explosive, especially when mixed vigorously. And now that I have had a decade to reflect on my transition from engineer to preacher, I think I know a few of the ingredients that became the unexpected chemical reaction that was, and is, my calling to preach.

My call to preach came, in part, through doing it—the infrequent opportunities to speak here, lead a Bible study there. And that makes sense; it’s a natural progression, I suppose. Someone sees something in you—some gifting, some potential—and eventually they ask you to give it a try. And it goes okay and you learn, and eventually someone asks again and you get another try. And then another. So, yes, I would say, in part, my call to preach came through doing it and the encouragement I received during those early years.

However, in large measure, my call to preach came not through doing, but having it done to me. What I mean is that the call to preach seemed to pounce on me, irrevocably so, while listening to other men preach and feeling my mind and affections doused in a kind of spiritual kerosene so that I just knew I wanted to, in fact had to, be involved in doing this for others. During the early days of this feeling, if I could have “hit pause” during a sermon by any one of a number of gifted preachers I was listening to in those days, I think I would have described the experience this way:

What God is doing right now, through that guy, on that stage, behind that pulpit, as he explains that passage, with those words and those gestures, and that tone, and with all of that love and passion and urgency, such that my heart is prodded and my mind is riveted—well someday, I just have to be involved in sharing that with others.

This is what I mean when I say that my calling to preach came not only through opportunities to preach, but also, even predominantly, through having it done to me. As I think back to the sermons that I was listening to in those days, I would say that this type of preaching made me say in my heart, “Yes! I want more of Christ; and our God is wonderful; and I’m so thankful for the Gospel; and now I too want to speak, and risk and serve and love and give my life for this Gospel.”

And this “reaction” to preaching still happens for me. Good preaching doesn’t get old. Still, as I listen to others preach (“that guy, on that stage, behind that pulpit, as he explains that passage…”), it still awakens longings.

So when people ask me why an engineer would ever become a preacher, I think they typically want a “sound bite” answer. And I’m not sure how to give them that. Someday maybe I will figure out how to do that. For now, I suppose that I could just say that it had (and has) something to do with vinegar and baking soda, corked and shaken.

[Image]

SEEING BEAUTY AND SAYING BEAUTIFULLY by John Piper (FAN AND FLAME Book Reviews)

A FAN AND FLAME book review of John Piper’s latest book, SEEING BEAUTY AND SAYING BEAUTIFULLY.

John Piper. Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully: The Power of Poetic Effort in the Work of George Herbert, George Whitefield, and C. S. Lewis; from the series The Swans Are Not Silent (Crossway, May 31, 2014, 160 pages)

Two years ago, I exchanged a few emails with a popular author (Peter Roy Clark). It stressed me out. Why? Because the author has published several books on grammar and effective writing. I must have reread my emails 10 times before hitting send. And maybe it’s just me, but more stressful than writing a short note to a grammar guru would be writing (and preaching) about three men that were brilliant at those very things—writing and preaching.

And this would be only truer when one doesn’t merely try to communicate the content plainly, but to simultaneously do it with beauty. Now that would be stressful. But is precisely what John Piper did in Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully: The Power of Poetic Effort in the Work of George Herbert, George Whitefield, and C. S. Lewis.

There is no way for me to know if Piper felt stressed as he wrote about Herbert, Whitefield, and Lewis. If he did, he didn’t say so. But I do know that if the central thesis of his book is correct—and I have found it to be true in my life—then if there was stress involved, we can be sure that there wasn’t only stress. For, as Piper argues, in the effort to say it beautifully, more beauty becomes visible.

And it’s this very point that is the central thesis of the book and the unifying theme across the lives of these giants of poetry, preaching, and prose:

“The effort to say freshly is a way of seeing freshly… The effort to say beautifully is a way of seeing beauty” (74).

Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully is the sixth installment in the series TheSwans are Not Silent. Most of the biographies in the series are adapted from hour-long messages at Desiring God’s yearly conference for pastors (links below). And for my part, this is where Piper is at his best—preaching to pastors.

In addition to the biographical sketches, there is a thoughtful essay on the proper, and improper, use of eloquence. The essay attempts to answer the question of when eloquence is helpful and honorable, and when eloquence is gratuitous, or just showing off.

But I should point out, that this book, like the conference messages it is derived from, is not just for those in the biz, not just for practitioners of words. Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully is for anyone that cares about their Christian witness, anyone that knows the power of language, and anyone willing to get in the trenches with words. For them, the work comes with a promise; namely, the effort to say it beautifully, there will be more seeing.

* * *

A Few Key Quotes

On George Herbert:

“The central theme of [Herbert’s] poetry was the redeeming love of Christ, and he labored with all of his literary might to see it clearly, feel it deeply, and show it strikingly.” (Piper, Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully, 56)

On George Whitefield:

“[Whitefield’s dramatic preaching] was not the mighty microscope using all its powers to make the small look impressively big. [His preaching] was the desperately inadequate telescope turning every power to give some small sense of the majesty of what too many preaches saw as tiresome and unreal.” (Piper, Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully, 95)

On C.S. Lewis:

“Part of what makes Lewis so illuminating on almost everything he touches is his unremitting rational clarity and his pervasive use of likening. Metaphor, analogy, illustration, simile, poetry, story, myth—all of these are ways of likening aspects of reality to what it is not, for the sake of showing more deeply what it is.” (Piper, Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully, 135, emphasis original)

On “poetic effort”:

“The point is to waken us to go beyond the common awareness that using worthy words helps others feel the worth of what we have seen. Everybody knows that. It is a crucial and wise insight. And love surely leads us to it. But I am going beyond that. Or under that. Or before it. The point of this book has been that finding worthy words for worthy discoveries not only helps others feel their worth but also helps us feel the worth of our own discoveries. Groping for awakening words in the darkness of our own dullness can suddenly flip a switch and shed light all around what it is that we are trying to describe—and feel. Taking hold of a fresh word for old truth can become a fresh grasp of the truth itself. Telling beauty in new words becomes a way of tasting more of the beauty itself.” (Piper, Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully, 144).

[In my first blog post, Fresh Words, Fresh Language, Fresh Blood, I say something just like this (“Taking hold of a fresh word for old truth can become a fresh grasp of the truth itself.”) It was affirming to hear Piper sing in harmony.]

Links to Conference Messages: Herbert, Whitefield, and Lewis.

[Image from CS Lewis' study at his home, The Kilns; photo by Mike Blyth]

Roadie Rage

We all experience rage. It’s natural. But does that make it (always) right? And more importantly, how we respond to our own emotions says a lot about us and our character.

A few years ago I submitted an article to a local periodical called the Tucson Pedaler. (Aside, I used to live in Tucson.) I’m not sure they are still publishing, but in the summer of 2011, they ran a short story about a cyclist who had an altercation with a car driver and they asked readers to send in their reflections about the story. So I did. I called it “Roadie Rage,” and they published it in the August/September 2011 Issue. For this week’s post, I have included it below. By way of background, a “roadie” is a cyclist that rides (primarily) on the road; for those that know nothing about cycling, think Lance Armstrong type bikes.

Because I ride my bike a few times a week, often near traffic, I am frequently reminded of my words in this article. In fact this morning, in snowy weather, let’s just say it is a remote possibility that I raised my voice to one particular car driver – a driver who was quickly too far away to hear what I said and who, naturally on a very cold day, had the car windows rolled up and would not have heard what I said anyway. And maybe that was for the best. Regardless, this morning I was reminded that I am a man still in need of God’s grace and that I long for the maturity of character to respond rightly to my own reactions.

* * *

Roadie Rage: Natural, but Wrong Nonetheless

I have a three-year-old son who loves to wrestle his dad. However, the other day when we were wrestling, he kicked me in the crotch.

I think it was an accident, but I yelled anyway. I reacted. Protective instincts took over. I pushed him away. There was a twinge of rage in my heart.

It all happened very quickly, but in a moment, I was reminded that I am fragile. I am vulnerable. I can be hurt. So I lashed out. But it was only natural, right?

Last week I read a police report about a cyclist who reacted; a cyclist who lashed out. Apparently the cyclist was cut-off by an absentminded motorist. At a stop-light, he caught up to the car and pounded on the passenger side door with enough force to leave dents. He broke the side mirror and promised in colorful words to do the same to the woman driver. “I will run you off the road and you will know how it feels,” he roared. From her cell, the women called 911, but before the police arrived, the perpetrator pedaled away.

What is uncommon about this event is not the close call between motorist and cyclist. Anyone who has ever spent time as a road cyclist knows such an experience – a car runs a red light; a large pickup truck brushes you back; a city bus zips by only to slam on its breaks while 30 tons jerk over into the bike lane to make a pickup.

Instantly, your blood boils. You see red. Obscenities spring forth as from a geyser. “Don’t you know that is how people get killed!”

Yes, we cyclists can ‘bob and weave’ in traffic with nimbleness, and can cover great distances at great speeds, but we often forget that we are wearing spandex and sitting on a piece of machinery weighing twenty pounds with only a helmet for protection. We are vulnerable. We can be hurt. So we lash out. It is only natural, right?

I suspect that most who read this harrowing account of the assaulted motorist, feel a measure of compassion for her, culpable though she is. Yet, I suspect a few, but still too many, read of the cyclist’s actions with vicarious pride. “Finally, someone stood up for us. Somebody did what I have never had the chance or courage to do myself,” they think.

As the cyclist put away his bike that day, safe at home, I wonder if he felt ashamed of his actions, as I did after I pushed my son away when he accidentally kicked me. Or perhaps, on the other hand, as he recounted the ordeal to his buddies, a grand satisfaction welled up regarding how ‘he showed her’. It is impossible to know.

In the end, while the cyclist’s actions (and ours) may be in many respects “natural” reactions – just as when a doctor taps you on the knee with a rubber, triangle hammer to check your reflexes, and you kick – we must conclude that what comes natural is not always right. Maturity and character are not always best assessed by what comes natural, but in how we react to our own reactions.

* * *

[Image from a picture I took on Thanksgiving Day 2014 riding Peter’s Mountain in Harrisburg, PA]